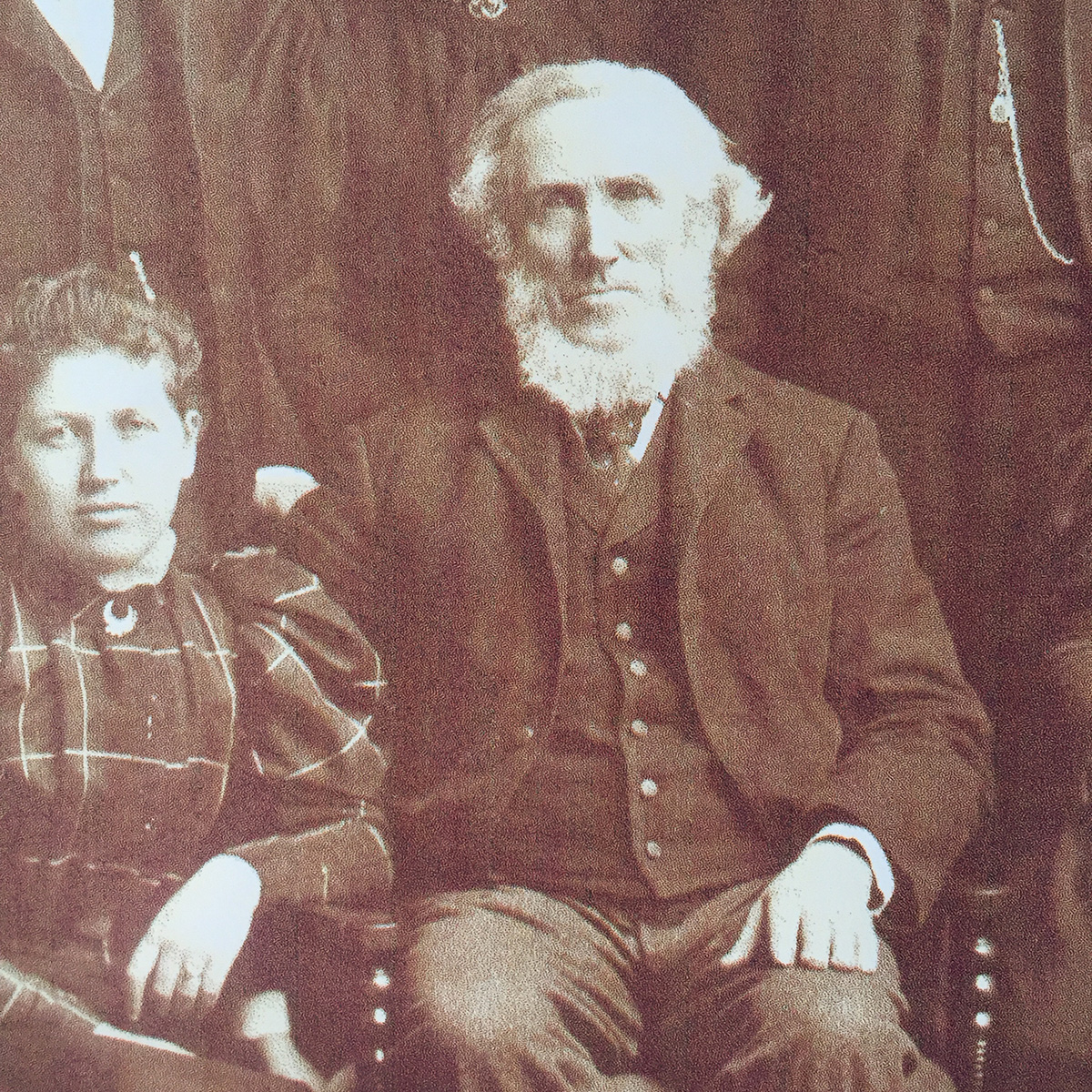

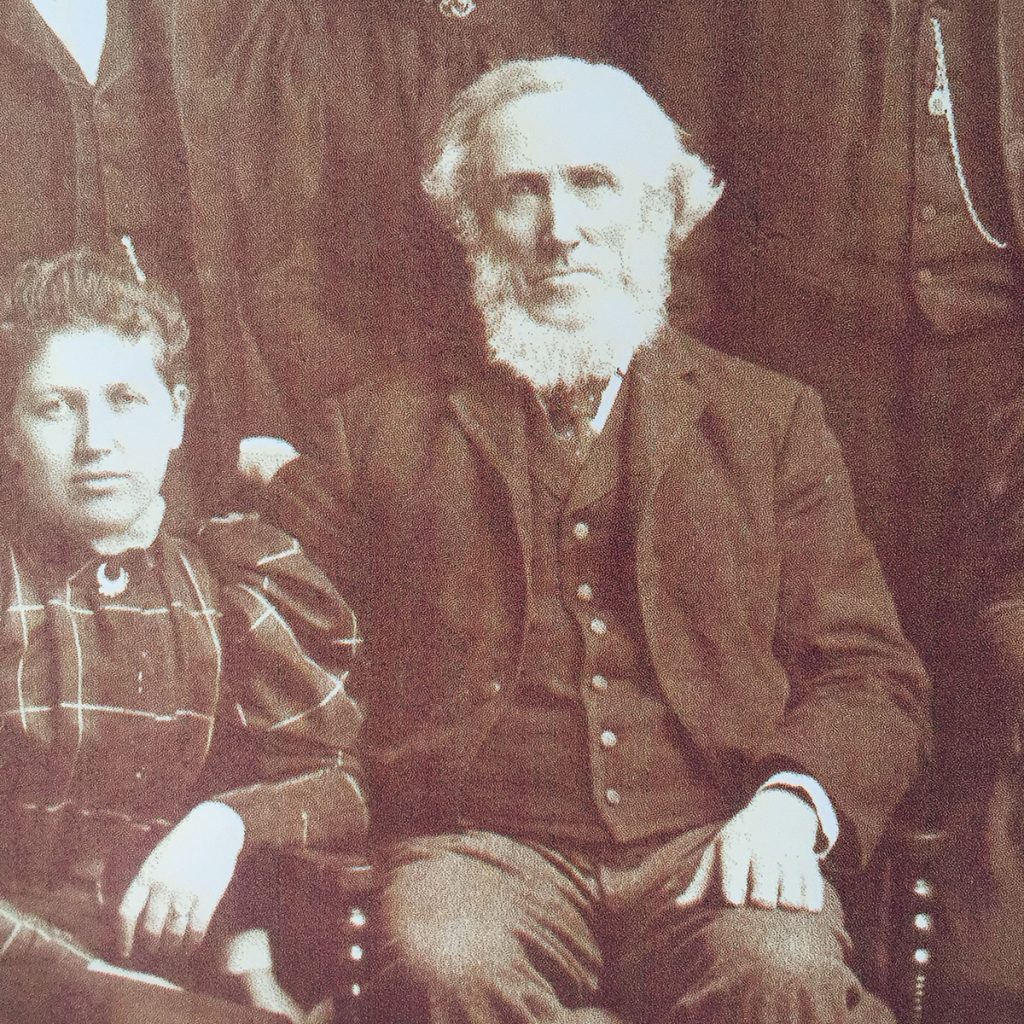

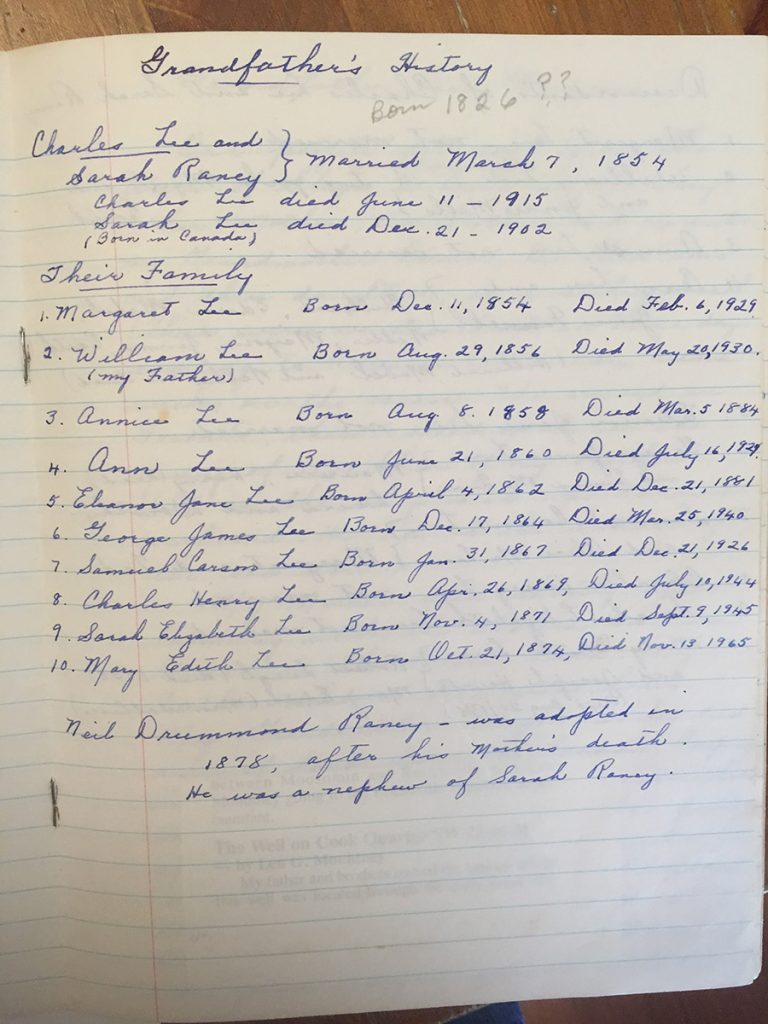

The memoir of Charles Lee – November, 1906

Recently, my son Spencer was assigned a family history project at school. While diving into our past, my mother (Spencer’s Gram Gram) provided us with this fascinating memoir, written by Spencer’s great, great, great grandfather Charles Lee.

The memoir describes many things, including his journey to Canada from Ireland, early farming techniques on the Canadian Prairies and, most poignantly, many unfortunate incidents that plagued his life.

Charles was 80 years old when he penned this memoir, and what strikes me is the flat candour with which he relates what must surely have been traumatic experiences. Perhaps it’s a testament to the “stiff upper lip” one was required to show in those hard old days; perhaps its a symptom of a 90-year-old mind that was coming loose at the hinges. Either way, the following is a fascinating read whether you’re related to Mr. Lee or not.

Charles Lee died nine years later, in 1915, at the ripe age of 89.

-Ryan Parton

The following memoir was penned by my great, great grandfather, Charles Lee

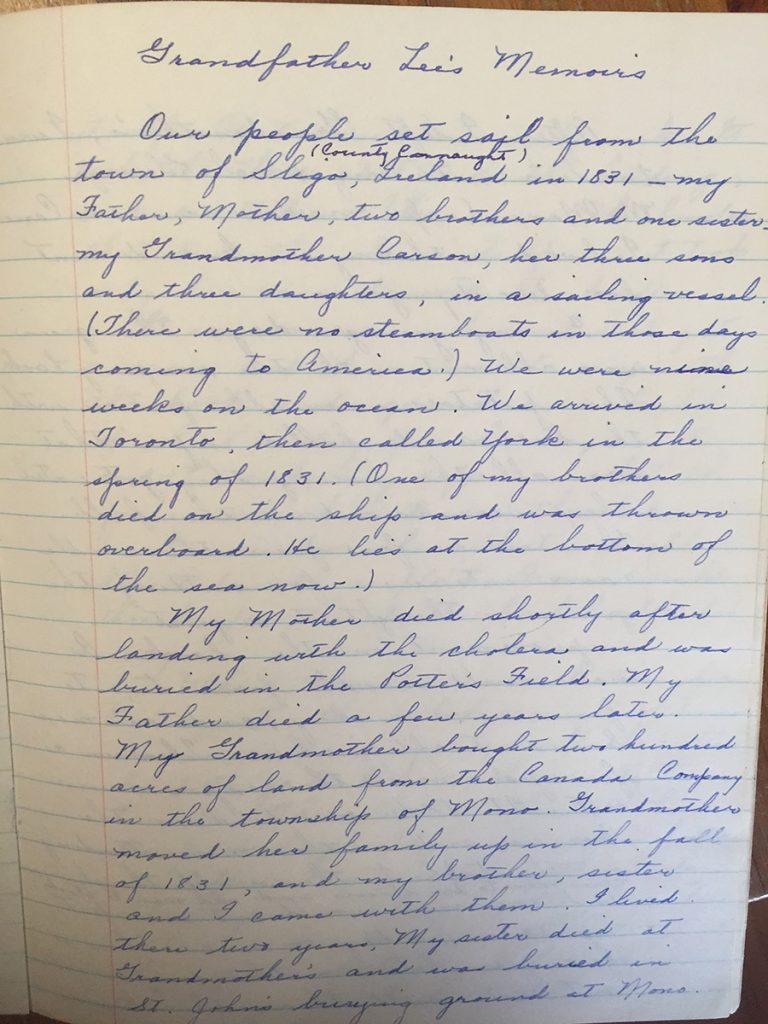

“One of my brothers died on the ship and was thrown overboard.”

Our people set sail from the tow of Sligo, County Connaught, Ireland in 1831 – my Father, Mother, two brothers and one sister – my Grandmother Carson, her three sons and three daughters, in a sailing vessel. (There were no steamboats in those days coming to America.) We were nine weeks on the ocean. We arrived in Toronto, then called York, in the spring of 1831. (One of my brothers died on the ship and was thrown overboard. He lies at the bottom of the sea now.)

My Mother died shortly after landing with the cholera, and was buried in the Potter’s Field. My Father died a few years later. My Grandmother bought two hundred acres of land from the Canada Company in the township of Mono. Grandmother moved her family up in the fall of 1831, and my brother, sister and I came with them. I lived there two years. My sister died at Grandmother’s and was buried in St. John’s burying ground at Mono.

After I left Grandmother’s, I went to live with my Uncle George McManus (wife’s maiden name was Carson.) I lived with my uncle and aunt for twenty years.

In my younger days the grain was all cut with the reaping hook. The potatoes were all put in with the hoe and hilled up – that was all the hoeing they got until they were raised in the fall. Then in a few years the cradle came into use for cutting the grain – thought it a great improvement on the hook. A man could cradle from two to four acres a day, and one man bound it after him. Then in a few years more the reaper came out. It took one to drive the horses, and another man standing on the table to throw off the sheaves, three men to the sheaves and one man to stook. One man would cut and put up 12 acres a day, or more. Then a few years later another reaper came out that would throw the sheaves itself. That saved one man’s work. It took the three still to do the binding, and a stoker. Then came the binder that tied the sheaves themselves – so it took only two men to work the binder.

It was common in harvest to get a man and hire him to reap with the hook, and give him a bushel of wheat a day for his wages as it didn’t make any difference what the price was when it was threshed.

I remember when wheat was all threshed with a flail. A man would thresh for the tenth bushel for his wages.

When there was an election for Parliament, the whole county of Simcoe was in one riding and all the voters had to go to Barrie, the county town, to vote. The election lasted three or four days. There were open houses in different places along the roads where you could get all you could eat and drink for nothing – at the expense of the men that were running for Parliament.

“The scripture was used a text book”

When I was nine or ten years old going to school, there was nothing only log schoolhouses with long planks with feet on them for seats, and no backs on them either. There was a board fourteen or fifteen feet long along the wall for a writing desk. The scholars all sat along the desk writing. The teachers got a certain amount from each scholar, and whatever the government grant would be for his salary. The teacher would board around about with the scholars. Each scholar had to bring a certain amount of wood to the school to help to keep the fire going. Reading, writing, spelling and arithmetic was about all that was taught, with a little history. The scripture was used a text book there.

In those days people would drive to Toronto with a yoke of oxen with a load of wheat or pork – with a sleigh, home-made without one bit of iron on it, only the chain that drew it. They would sell their pork at three or three and a half dollars per hundred. It would take them three days to make the trip and be out a good part of the night at that. Always in the winter they drove to Toronto and sometimes there would be six or seven sleighs in a drove. Each man would have a long gad that he would reach the oxen behind the sleigh. Although I did not do it myself I saw it done.

In 1849 I bought a hundred acres of land without a tree cut on it. That fall, I built a little log house eighteen by twenty and one story high. I chopped ten acres that winter and red it up the next summer and put in fall wheat. I sold the wheat for fifty cents a bushel. I kept batch for four years, and chopped ten acres every winter, and every fall sowed fall wheat. In the winter I bought rails and hauled them for to fence it with in the spring.

“We raised a family of ten – four boys and six girls – all alive at present, only two girls that died.”

In 1834 I got married and chopped ten acres that winter. We thought it fine fun to see ten acres of log heaps all burning at one time. If I had the timber I burned then, it would be worth the price of the farm now. I teamed wheat to Bolton village, Woodbridge, Weston, Humber and Toronto the time of the Russian War and sold it for $2.12 and a half a bushel. I bought a span of horses and three hundred and fifty dollars for them. The first wagon I bought for ninety dollars. The first cow – I bought her and her calf for thirteen dollars. She was a good one too.

We raised a family of ten – four boys and six girls – all alive at present, only two girls that died. (They were eighteen and twenty years old.) Twelve was a pretty big family at the table every meal.

In my early farming days all grain was sown by hand. And let me tell you it was pretty hard work carrying twenty or twenty-five pounds of wheat in a pail or box the most of the day. The harrowing was done with a V-shaped harrow with iron teeth. I saw them with wooden teeth – they were handiest to work among the stumps. And when we would sow turnip and broadcast – we would cut the top off a bushy tree and harrow in the seed with that.

So you may think we had a lot of fine implements to work with. There were no loaders then – only two-legged ones. The first ten acres I chopped I made a bee and got pretty near all of it done in one day. Then came the burning and clean up to make it ready to sow the sees. And then you would have to wait nine or ten months before you could get any money for your work.

“A tree fell on her and killed her dead”

In my young days, the women would be out hoeing potatoes or some other work – with their baby lying in a sap-trough for a cradle beside a stump. How would the young women like to do that in these days? I and my Aunt Susan Carson were out boiling sap to make sugar sometime early in the forties. A tree fell on her and killed her dead and she never spoke. My uncle took her home to the house on his back. I remember that day well, although so long ago. And another time a (McManus) cousin and I were out boiling sap and the kettle fell off the fire and her legs were badly scalded. So I had to carry her home to the house. (She was only five or six years old then.) Another day I was chopping wood at the house and my cousin, John McManus, came behind me. I did not see him and the axe struck him and gave him a bad cut.

One incident more – uncle sent me to the Grist Mill at Mono Mills with a bag of wheat to get ground into flour. Mr. Potter of Caledon came a few minutes after me. He asked me to give him my turn as he had farther to go than me, and if I would come to his house he would give me some apples to bring home. So I got on horseback the next Sunday with a pillowslip in my jacket. He was very glad to see me. He gave me my dinner and all the apples I could eat. He asked me if I could read. I said “Yes.” I read a chapter in the New Testament for him and he said I was a very good reader. He said, “I suppose you came for the apples.” I said, “Yes.” “Well” he said “I wonder your uncle let you come on the Sabbath Day. But if you will come on a weekday, I will give them to you.” He was a strict Sabbatarian. Apples were very scarce in those days.

So here I am now, living in Orangeville, and by the Grace of God, enjoying good health and in my eightieth year – after all I came through.

Charles Lee

November 1906